It Says Nothing To Me About My Life

As May Day settled into evening, I sat in a pub garden with a friend. Clouds of pollen danced in the slanted sunlight. We were talking about all the flags: the sheer fucking omnipresence of the Butcher’s Apron, all across London, its nasty faux-cheerful colours assailing us over and again, like a punch in the gut. Ever since last year’s Jubilee, and the subsequent death of Elizabeth II, every last apparatus of the British state has been engaged in a desperate project to make flagwaving jingoistic monarchism happen—but (at least as far as my friend and I could tell) to little avail. The general attitude towards it all is best summarised as a sort of collective s h r u g, a disengaged resignation: oh, it’s raining again; oh, the flags are out again.

This general indifference (so general that even Vincent Bevins has seen fit to remark upon it) seems to prevail almost everywhere—other, perhaps, than amongst columnists and intellectuals, including those of the (broadly-defined, often self-identified) left. For the last 12 months, we’ve been treated to periodic flurries of comment and analysis re. the National Mood—a trend that found its peak in the endless pontificating about The Queue. Sometimes it feels compulsory to join in: I begin to wonder if I’m failing in my responsibilities as a writer by not producing my own tepid take on What It All Means. But when I try to reflect on this question of meaning, I find myself echoing Zhou Enlai: “it’s too soon to say.” It seems to me that the meanings and effects of this moment will likely not be visible to those of us who are living through it. History is a multivalent thing; at once the flicker-flash of the decisive moment and the slow tectonic flow of the much-vaunted longue durée. We cannot know at what speed the dust will settle, nor where it will fall—nor precisely how much dust was even cast into the air anyway. All remains open, all remains to be seen.

And so the essayist who would look into a crowd of mourners, or a succession of funereal billboards, or a string of Coronation bunting and hope to see—with clarity and directness—something of historical import will, I think, see only herself: her own assumptions, her own preconceived notions, her own ideas of who people are, in an endless cycle of affirmation; like Narcissus, who mistook his own reflection for the truth. If all remains open, better to also remain open; better to accept that I am a part of what happens, and no Olympian perspective, no god’s-eye view, is (or ever can be) mine. Anything I can say will necessarily be provisional—a snapshot, a sketch, an attempt (and only ever that) to think both with and within the times.

And I’m not sure whether, in the end, I really have much to say. I suppose, ultimately, I’m just extremely suspicious of any attempt to reduce people to a set of simple propositions; to read political or ideological content into certain activities, and then extrapolate that any participant must therefore hold x or y belief. It’s extremely syllogistic: all members of the coffin queue are enthusiastic monarchists. Socrates is in the queue. Therefore Socrates is an enthusiastic monarchist. And, like most syllogisms, it relies on question-begging:

Person A: All members of the coffin queue are enthusiastic monarchists.

Person B: How can you be certain?

Person A: Well, because they’re in the coffin queue.

Is it really so simple?

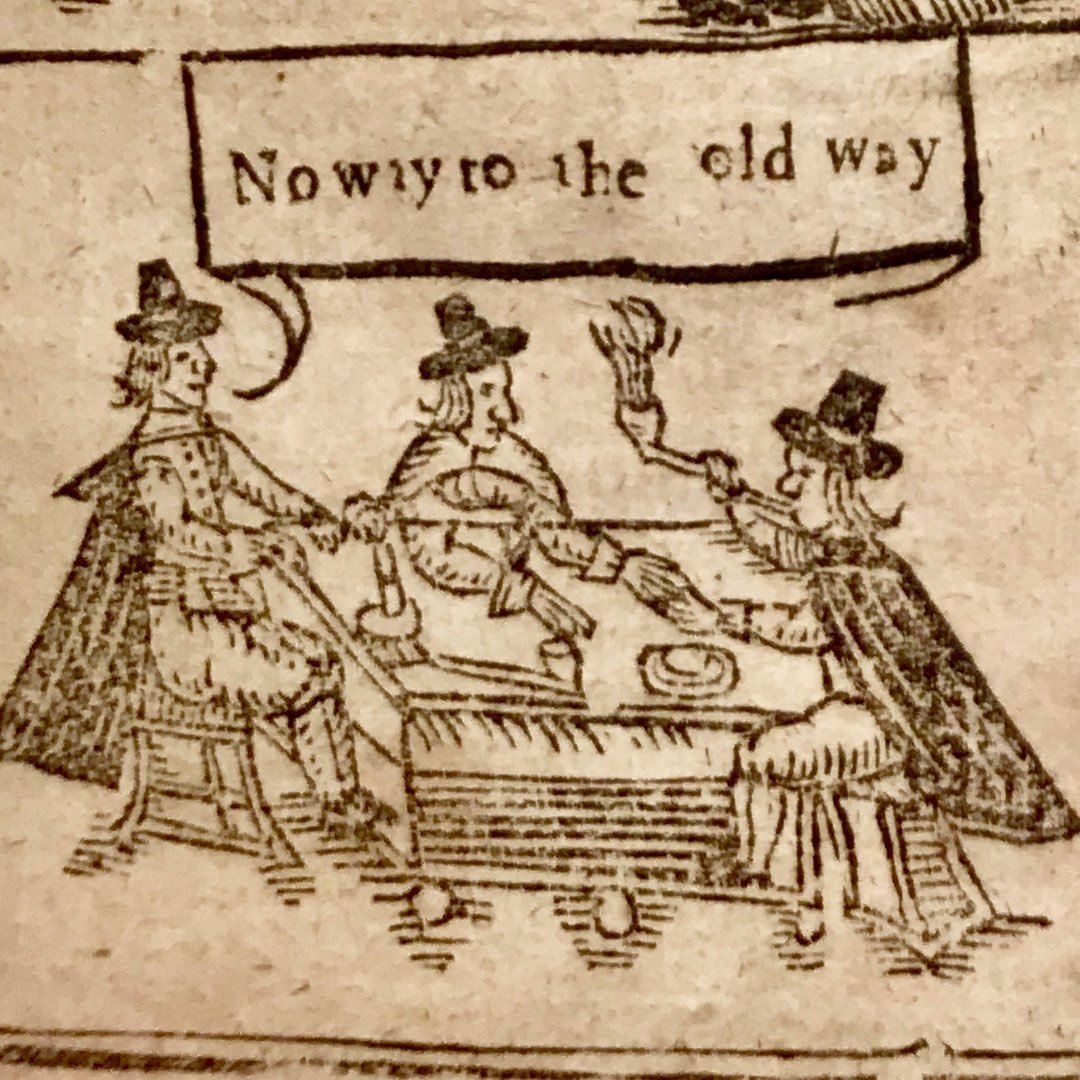

I did not join The Queue, but I can understand why a person who is indifferent to the monarchy may have done so. It’s not every day you get to see a dead queen in a box. It’s not every day you get presented with the opportunity to witness and participate in what was (however much I might wish it otherwise) a world-historical moment. Something to tell the grandkids about. I can even understand why a person who is vehemently opposed to the monarchy may have joined The Queue: there’s a grim catharsis in taunting your deceased enemies, in seeing even the mightiest oppressor brought low by death. One could not very well argue that every person who turned up to the execution of Charles I was a monarchist, just as it is doubtful that everyone in attendance was a committed Parliamentarian. Some may have wanted only to see the spectacle, to bear witness to history—to have a story to tell. If some writers will insist on presenting as evidence the existence of celebratory ‘traditions’ that were in actuality dreamt up in the time of Victoria in response to a perceived public anti-monarchism; if they will keep pointing to the coronation of Elizabeth II, as though society and culture has remained immobile for 70+ years, then one can only assume that all of history is fair game for analogisation. Pitch idea: What does the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 tell us about the coronation of ‘King Charles III’? It’s a pretty glib and silly point, sure—but no more glib or silly than such reductive assertions deserve.

If we can grant Stuart Hall’s point that people, under capitalism, do not tend to live their conditions “transparently, ‘authentically’”, then surely we can accept that people do not always act for immediately intelligible, transparent, ‘authentic’ reasons? It’s a bit like believing that Sun front pages are a direct broadcast from the Atavistic Proletarian Hivemind, as opposed to an attempt to influence people into understanding their experiences in certain ways.Why do so many ideologues and would-be ideologues on the left appear to be intensely committed to a sort of Pavlovian model in which all actions are nothing more than simple responses to given stimuli: a given input leads to a single, ‘pure’ behavioural output? I suspect the answer is twofold.

Firstly, because (to borrow from Raymond Williams) this “way of seeing people as masses” is a deeply-ingrained part of how petty-bourgeois, bourgeois, and posh people see the world, and because, for all sorts of reasons (as I recently wrote about) these people are massively over-represented on the part of the left that is able to speak, write and think in public. This becomes a self-reproducing worldview, because if proles can in fact think for ourselves; if we are not their flock, waiting patiently to be led along the righteous path of socialism; then how can the left (petty-/)bourgeoisie and gentry justify their own existence and continued ascendancy?

Secondly (and relatedly), such a view tends only ever to affirm their own diagnosis of the situation—something that we see repeating over and again, from Marxist-intellectual-turned-eco-shock-jock Andreas Malm treating commuter rage against disruptive climate protest as being axiomatically working class, to every single left ‘think’-piece about the Jubilee, the Queue, etc etc etc. In an insightful essay from last September, Tom Gann takes aim at this “national nihilism” and its deployment of a “fetishistic national subject”. This approach, he writes, “entails a certain trust in appearance, that when exposed to enough expertise, appearances quite unproblematically disclose what is real”. Moreover, it allows “the question of class” to be “collapsed into posh people ruling”—a slippage first identified by the Diggers in the time of the ill-fated Charles I, and undoubtedly a useful one for those left ideologues invested in guarding the gates of their own positions and careers from attack by gobby proles who would dare to think and speak for themselves. Gann draws on the Greek Marxist theorist Nicos Poulantzas to show that the question of political power in Britain is by no means as simple as these arguments make out. And indeed, how could it be, when the so-called ‘King’s Champion’, Francis Dymoke, whose forefathers have held this feudal position since at least 1377, is both “34th Lord of the Manor of Scrivelsby” and a chartered accountant?

Meanwhile, for all my broad agreement with the sort of common-sense republicanism that often underpins left comment on matters monarchical, I have to say that it sticks in my lumpen, atavistic, proletarian craw to be lectured, however mildly, on the “gross” and “racist” features of an hereditary system of privilege by somebody like, for example, Adam Ramsay, whose family have owned their estate since 1232 (when it was “given to an ancestor by King Alexander II of Scotland as a reward for saving his life”). We fucking know it’s gross, lad. Some of us have been living in the grossness for generations. If, as Ramsay argues, “Anglo-British nationalism is a story whose moral is that posh people should rule,” it is just as much a story about posh people’s assumed right to speak and to be heard; about who has both the material and the cultural support structure to enable them to write, and to write publicly, and for that writing to be recognised, appreciated, and perhaps even remunerated. Attacking the very specific hereditary structures of the monarchy is a very efficient (albeit, I suspect, unintentional) way of deflecting attention from the deep networks of patronage, privilege, and exclusion that help to cohere and reproduce the entire British class system, of which monarchy is just one aspect. [An aside: I find Ramsay’s delineation of an “Anglo-British” nationalism incarnated in the monarchy somewhat curious, given a) the Union of Crowns, b) that Scotland was an equal party to the Acts of Union, which began life as a diplomatic treaty, and c) Scotland’s enthusiastic participation in British imperialism and colonialism, including in Ireland.]

To put it in Deleuzian terms (that is, to run the risk of making Labour lose Blyth Valley once again), the assumption that once the British monarchy falls, so too will the British class system (not to mention the global class system set into motion by British imperialism) seems to rely on an arborescent model of thought: hack away at the roots and the whole tree will fall. I rather feel, however, that the British class system is best understood using Deleuze & Guattari’s model of the rhizome (set out in Mille Plateaux; I’m quoting here from Brian Massumi’s translation): “a plane whose elements no longer have a fixed linear order” which “operates by variation, expansion, capture, conquest, offshoots.” Its “fabric”, they write, “is the conjunction: ‘and… and… and…’”. Class, in Britain, is this and this and this; it is economic and cultural and structural and conjunctural and generational and fluid… and… and… and…. Because of this, the simple notion of “making a clean slate, starting or beginning again from ground zero,” or even “seeking a beginning or a foundation” is a fruitless task. There’s no one weird trick to unmaking class relations in Britain—which isn’t to say that it can’t be done, but only that it will be complicated, slow, and uncomfortable, and will require (as the Diggers and Ranters knew) an unshakeable commitment to practice, and to relinquishing the fruits of oppression. Such a relinquishing will need to be undertaken not only by the ‘left gentry’ (ie. Ramsay et al), but also by the (petty-)bourgeois types who comprise the vast majority of left commentators, many of whom are also enthusiastic participants, in their own way, in this ongoing festival of national nihilism (which is, as EP Thompson cautions, its own form of British exceptionalism).

All of this to say that incessantly, self-satisfiedly regaling the world at large with tales of all these stupid masses lapping clownishly, happily, at their flag-emblazoned, state-mandated bowls of Monarchist Gruel™ is probably not going to do very much to bring about real revolutionary transformation for the people who need it. Particularly not when the people who need it are, at least subtextually, coterminous with the imagined clownish gruel-lappers.

We like to consider ourselves above making up a guy to get mad at, and letting him ruin our day. We also like to consider ourselves above inventing the sorts of demographic imaginary friends conjured by political consultancies: Stevenage Woman, Workington Man (sidenote: why do they always make them sound like bog bodies?). So why are we giving so much airtime to people who are, effectively (albeit not ostensibly… yet), inventing Queue Man, or Coronation Woman? Especially when, as Vincent Bevins put it, the whole thing “really has the weird vibe of a mandatory office party”? For a lot of people, as Tom Gann observed, the death or coronation of a monarch probably doesn’t mean all that much at all. The Met Police, meanwhile, have posted a series of sinister tweets that seem to threaten a ramping-up of repression over the weekend—should this come to pass, it will certainly mean far more for most of us than a rich man getting some colonial perfume poured on his head.

To be clear, I’m not saying that this general collective indifference is necessarily a good thing. I was raised by committed republicans and my instincts, like a compass finding north, always wheel back to Righteous Ire. People should be angry about the class system. People should be angry about the Butcher’s Apron (which holds a similar place in history to the US Confederate flag, as far as I’m concerned). People should be angry about the monarchy, and the ruling class, and particularly about Charles. But there’s a huge gap between not being angry ‘enough’ and actively supporting. And in that gap, if our ideologues choose to look for it, lies the opportunity to really see, to really listen; to stop telling people who and what they are, and instead offer our attention, with humility, to the actual texture of things as they are lived, experienced, felt, and understood. If the flags and the bunting and the canned narratives about lives of public service and dedication to their people say nothing to me about my life, neither do the thudding insistences, at once gloomy and smug, from Men of the Left that ‘the nation’ (whatever that is) holds the monarchy in ‘a passionate embrace’ (whatever that means).

Perhaps they’ve seen something I haven’t. Or perhaps their examining lens, their form of thought, will always lead them to this sort of conclusion. For my part, I feel less as though I’m witnessing some servile populace who spend most of their lives residing in some Barratt Home (or whatever snobby signifier we’re currently using) version of Plato’s cave, and more as though I’m witnessing an extremely rattled state desperately trying to make a 21st century flagwaving jingoistic monarchism happen. It’s not going to happen.